|

|

|

|

|

As early as the mid to late

1300s, protests against the Roman Catholic Church in Europe emerged

through the influence of men like John Wycliffe

in England and John Hus in

the area that became the Czech Republic.

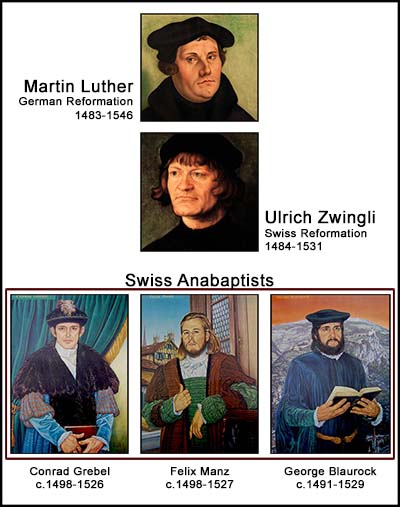

But it was Martin Luther in Germany who consolidated reform efforts into the movement known as the Protestant Reformation. And Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich, Switzerland, a contemporary with Luther, led a reform movement in Switzerland. The French theologian, John Calvin, fled to Geneva, Switzerland and spread reformation ideas from there. A disciple of Calvin, John Knox, established a reformed branch of Protestantism in Scotland. Each of these reformers espoused some of their own unique teachings, but there were some major reformation doctrines on which they all agreed:

Thus, Protestant reformers rejected many of the teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. But none of these reformers took the step to separate the church from the authority of the "State" (the ruling government) and none of them questioned the practice of infant baptism. |

|

Zwingli and the Swiss Reformation While still a Catholic priest, Ulrich Zwingli began to study the New Testament seriously. When he became the "people's priest" in Zurich in early 1519, he resolved to preach nothing but the Bible. That, in itself, was revolutionary for a Catholic priest! Very soon the city council in Zurich authorized Zwingli's evangelical preaching and several gifted young intellectuals were attracted to him and his study of the Greek New Testament, Greek being the original language in which the New Testament was written. By 1522 this group of young men had become zealous for reforming the Catholic Church, just as much as Zwingli was, based on the teachings of the New Testament. They opposed such things as the Catholic doctrine of mass, the sale of indulgences, celibacy of priests, the doctrine of purgatory, and images in the church building. By 1523, the City Council of Zurich determined that Zwingli should receive his salary from Council and not the Catholic Church. This was the first official step between the separation of the "Reformed Church" from the Catholic Church. Rise of the Anabaptist Movement Two of the young men in Zwingli's Bible study group were Conrad Grebel, whose father was a member of Zurich's Great Council, and Felix Manz, a bright young Greek scholar. In October of 1523, in the second of two disputations in Zurich between leaders of the reformed movement and the Roman church, Zwingli chose to leave it up to the city magistrates of Zurich to decide when to discontinue the Roman practice of mass, in favor of a simple memorial of death of Jesus. Grebel, Manz, and others from Zwingli's group of New Testament students were greatly disappointed--even outraged--that Zwingli appealed to the authority of the Council rather than obeying the authority of Scripture. By January 1525, a former Catholic priest Jörg Cajakob (who became known as George Blaurock) had joined Grebel and Manz in Zurich, from his home canton in southeastern Switzerland, and took up their cause with great zeal. Zwingli's attempts to calm his former disciples failed and a disputation was scheduled for Zurich in January 1525 to try to settle the differences between Zwingli and Grebel, Manz, and their friends. The Council proclaimed Zwingli to be the winner of the dispute and gave the young radicals three options: 1. conform, 2. leave Zurich, or 3. face imprisonment. To this point, the Roman doctrine of infant baptism had not been a central focus of the controversy, but that changed soon after the January 1525 decision by the Council. Even Zwingli had questioned the Roman Church's doctrine that infants needed to be baptized in order to be saved. As Grebel and others in the little group thought more about the New Testament's teachings, they began to realize that the church in the New Testament consisted of people who had placed their faith in Jesus Christ for salvation prior to being baptized. And they saw no clear evidence of infants being baptized. This, apparently, had been a conviction that had been developing in their thinking for several months. Then on the night of January 21, 1525 these young radicals took a very radical step in extending the reformation to its next level of consistency with the New Testament. In a prayer meeting in the home of Felix Manz, George Blaurock...

From this time forward, adult baptism based upon a confession of faith in Jesus Christ became the central tenet of faith for the people known as Anabaptists (re-baptizers), the label assigned to them by their enemies. The anti-Zwinglians preferred the name "Swiss Brethren," but the name Anabaptists stuck with them. When these Anabaptists began to baptize other adult believers in the villages of Zurich and refuse to have their own children baptized as infants, Zwingli and the Zurich Council responded with harsh persecution. To the Catholic Church and the Zwinglians, failure to baptize an infant was a serious offense because the salvation of the infant's soul depended on it. Also, refusal to do so was civil disobedience--rebellion against the State. Persecution of the Anabaptists Anabaptist teachings quickly took root among a group of farmers in the village of Zollikon, about six kilometers southeast of the city of Zurich. A church was formed there when some of the farmers submitted to believers baptism administered by Blaurock and Manz and began meeting regularly to participate in New Testament studies and simple observances of the Lord's Supper. On Monday, January 30, 1525 city police arrived in Zollikon and arrested Blaurock, Manz and all of the farmers who had been baptized in the past eight days. That was just the beginning--the beginning of nearly 300 years of persecutions for Anabaptists in Switzerland. Unfortunately for the early Swiss Brethren, Conrad Grebel, often called the "Father of the Anabaptists," died of the plague within 20 months after the origin of the movement. Felix Manz became the first martyr for the Anabaptist cause. He was executed by drowning on January 5, 1527 in icy waters of the Limmat River in Zurich. On the same day Manz was martyred, Blaurock was mercilessly beaten in Zurich and expelled from that city. On September 6, 1529 he was burned at the stake in what is now northern Italy. Many other Anabaptists suffered horrendous physical torture, suffered long or died in prisons, were executed, or were forced to abandon their property and be exiled from their Swiss homeland. Executions of Anabaptists ceased in 1614 in Zurich, but persecutions did not end with the death of the last martyr. Other forms of oppression continued for many years. Following the deaths and exiles of its early leaders, by 1535 the Anabaptist movement was subdued as a mass movement, by Zwingli and the Reformed Church in Zurich. But Anabaptists were not eliminated there and the movement spread to Bern (Switzerland) and to many other parts of Europe, especially to the Netherlands and southwest Germany. Menno Simons (1496-1561), a former Catholic priest converted to the Anabaptist faith in the Netherlands and soon emerged as a leader of the movement there. Because of his strong and able leadership, the name "Mennonites," (or "Menists") gradually replaced the name "Anabaptist" beginning in the latter decades of the 1500s, especially in the Netherlands and other countries to which these people dispersed. Emigration from Switzerland During and following the Thirty Years' War that raged between Protestants and Catholics in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, the oppression of the Anabaptists in Switzerland was revived and intensified. In 1657, for example, there were 170 Anabaptists in Zurich prisons. Hundreds of Anabaptists were deported or emigrated northward down the Rhine River into parts of southern Germany. An estimated 1,661 Anabaptists fled from Canton Zurich in the 1650s. Seven hundred helpless and impoverished Swiss Anabaptists were driven from their homeland in 1671. By 1700 few of them were left anywhere in northern Switzerland. True religious toleration was not granted in Switzerland until the early 1800s. Sources for the general Anabaptist history information above, see the Resources page on this site.

|

||

|

|